In the News: ‘Fiscal Sponsorship Is On the Rise’ by Eden Stiffman

A closer look at fiscal sponsorship authored by Eden Stiffman for The Chronicle of Philanthropy: https://www.philanthropy.com/article/fiscal-sponsorship-is-on-the-rise-allowing-groups-that-arent-nonprofits-to-accept-donations?sra=true

New Report: Fiscal Sponsorship on the Rise, Stewarding Billions of Dollars for Diverse Nonprofit Programs and Expanding Shared Infrastructure and Capacity Building

PRESS RELEASE. Philadelphia, Pa.—Fiscal sponsors are a significant part of the nonprofit funding ecosystem, showing rapid growth in the last 20 years, stewarding billions of dollars in community investment, and providing critical back-office infrastructure to diverse nonprofit programs. Those are among the key findings in a new report released today by Social Impact Commons and the National Network of Fiscal Sponsors (NNFS). This report is the first of its kind in more than 17 years, providing a significantly updated picture of the role fiscal sponsors play and how they can support greater growth and impact.

A fiscal sponsor is a nonprofit organization that provides diverse nonprofit initiatives with access to charitable funding and additional shared support, including corporate structure, finance, HR, legal, insurance, risk management, and other resources. Nonprofit organizations and initiatives partnering with fiscal sponsors can then capitalize on these shared resources and focus more of their efforts on their mission. The new report is based on survey responses from 100 fiscal sponsors, conducted during 2022 and 2023.

Collectively, the 100 sponsors that participated stewarded over $2.6 billion in community investments in the previous year. Other key findings from the report include:

The last 20 years have seen larger growth in the field than the previous 50. Nearly three quarters of respondents (73%) were formed since 2000. Leading this growth were a majority (53%) locally and regionally focused sponsors, working within the communities they serve, followed by sponsors with a national (38%) and international (9%) geographic reach. Most respondents (58%) were medium to large in budget with expenses between $1 and $50 million.

Fiscal sponsors and their project leadership exhibit appreciably greater race, gender, and other demographic diversity than the general nonprofit sector, comparing the field scan data with broader sector data collected by the Candid organization.

Sponsors are expanding beyond basic back-office support. Finance, HR, legal, insurance, and compliance are still among the most offered by 73% of respondents, but many sponsors are also offering capacity building development support (61%) and strategic financial advice (49%).

Demand for fiscal sponsorship currently exceeds supply of sponsorship programs. Roughly one in four respondents, 28%, reported that they temporarily suspended or stopped new project intake, and 62% reported that they need to recruit additional staff.

“Fiscal sponsors are a large and growing part of the nonprofit landscape,” said Thaddeus Squire, Chief Commons Steward of Impact Commons. “They provide a wide range of support and guidance to the projects they sponsor, and our research shows they sponsor projects with very diverse leadership. Nonprofit organizations of all types should consider fiscal sponsorship in developing their programming, funding, and overall business model development. 76% of the organizations that responded to our survey offered fiscal sponsorship alongside other programs, indicating that fiscal sponsorship, as shared infrastructure, is also a potential business model for nonprofits.”

In addition to the field scan, Social Impact Commons today will be releasing a vision for the fiscal sponsorship field, focusing on a broader collaborative approach to nonprofit infrastructure sharing, called management commons. This vision would ultimately result in fiscal sponsors providing more equitable access to nonprofit leaders, building shared resources for particular areas of charitable work, geographic regions, and cultural groups.

Fiscal sponsors would ultimately provide much of the shared infrastructure nonprofits need in a more financially sustainable manner, offering a long-term alternative to stand-alone nonprofit operations and enabling individual nonprofits to be laser-focused on mission. In a broader sense, the practices of nonprofit resource sharing at the core of management commons could also apply to any nonprofit organization, suggesting a fundamental shift in the sector toward more collective action and solidarity economy solutions.

Earlier research by Social Impact Commons and cited in the position paper showed that nonprofits’ “overhead” operating costs were 50 percent lower when using fiscal sponsors compared to operating independently. If those savings were applied across the nonprofit sector as a whole, it could mean reallocating tens of billions away from administrative costs toward front-line programming per year.

“Building the management commons is essential to enabling the overall success of the nonprofit sector,” said Neville Vakharia, board chair of Impact Commons. “This approach has benefits on scale, efficiency, justice, and sustainability. We must collectively work to create this infrastructure to truly move toward social justice.”

The survey that formed the basis of the field scan was conducted between November 1, 2022, and March 31, 2023, with 100 sponsors responding substantially to all parts of the survey. The respondents were diverse in many ways. Respondents came from close to 20 different states. Half managed fewer than 30 sponsored projects, but 18% managed more than 100 projects. The field scan was self-funded by Impact Commons and NNFS. Impact Commons was able to lead this work with generous operating support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Fidelity Charitable Trustees’ Initiative.

One Project with Two 'Model A' Fiscal Sponsors? That's One Too Many! by Colibri Sanfiorenzo Barnhard and Josh Sattely

We (HASER and Social Impact Commons) are occasionally asked whether it is advisable or even allowable for one nonprofit project to have multiple ‘Model A’ fiscal sponsors at the same time. Below, we share our perspective on this question in English and here, our partner HASER has posted a version in Español. We’ll save a nuanced analysis of the same question applied to ‘Model C’ relationships for a future post.

Model A Relationship:

‘Model A’ Comprehensive Fiscal sponsorship (also called “Direct Fiscal Sponsorship”) is an arrangement where an exempt organization, typically a 501(c)(3) public charity, furthers its mission by sharing its legal home and back office infrastructure with mission-aligned “Projects” while retaining the discretion needed to ensure compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Back office infrastructure includes but is often not limited to: tax and regulatory filings, financial and grants management, compliance, the ability to hire staff, asset management and liability insurance. A simple way of looking at the relationship is - the Project becomes a program of the nonprofit but there are defined roles and responsibilities as to how the nonprofit supports and works with the program with maximum allowable strategic and programmatic decision making sitting at the Project level.

Through this relationship, Project leaders can raise money and carry out their work in a compliant and supported manner.

Thorny Questions for Multiple Sponsors

Although not prohibited by law per se, because a Model A project is, legally speaking, a program or initiative of a nonprofit, it is highly unusual and generally not recommended that a Model A project use multiple fiscal sponsors as it raises a host of problematic questions:

Transparency Questions: One program housed at two organizations is confusing to the public and regulatory agencies. Donors understandably want to know where their money is going and the Attorney General or equivalent regulatory body of each state and territory is charged with ensuring donors are not misled and nonprofits are transparent. If there are two homes for a program, how do donors decide which one to donate to? How do donors understand the full picture of the organization when its finances and overall structure are bifurcated? If a confused donor raises concerns with the Attorney General, are both organizations investigated?

Operational Questions: Each fiscal sponsor will have its own policies, process, and expectations around the relationship. What policy and procedure applies and in what instances? How are conflicts resolved? What programs and or operations sit where? How does the leadership of the Project even juggle all this?

Financial Management Questions: How do the sponsors and the Project understand the full picture of the organization when its finances and overall structure are bifurcated? How is it determined who applies to what funding sources? What is shown in proposal budgets - combined budgets for each project budget at each sponsor or just one? How could either sponsor ensure the same costs are not reimbursed by the other sponsor? Are certain costs cross shared across the entities? How are those managed and distributed? Who holds the overall responsibility over grantees and vendors? Are revenues in certain cases documented twice too?

Employment Questions: Who hires who and why? Who makes independent contractor v. employee determinations? If some Project staff are hired by one sponsor and other staff hired by the other, are salary scales and benefits packages aligned? If not, is that equitable? How are computers and other assets managed, supported and protected? How are legally sensitive and confidential employment matters handled? And how is supervision of staff managed, if they are spread across multiple entities?

Legal and Risk Management Questions: One program housed at two organizations creates thorny legal and liability questions. Who’s the fiduciary for what? Who is ultimately responsible for the finances and operations of the Project? Is there one or two advisory boards? Who holds title to assets such as IP and equipment? How is that decided? Is there a license or partnering agreement defining how they are managed for the benefit of the Project? If something were to happen, who is liable? Do both organizations get sued? Which insurance policy would respond? What happens if one sponsor terminates the relationship and there are active grants and liabilities on that side?

Resolving all of the questions posed above (and others!) requires a tremendous amount of time and attention of the Project leadership and both sponsors on the front end, as does actively managing a split relationship of this sort once established. As such, we do not endorse these set ups and recommend that fiscal sponsorship agreements make clear that the ‘Model A’ Project may not have multiple sponsors simultaneously.

**The information provided by Social Impact Commons and HASER does not constitute legal advice. Social Impact Commons and HASER are making this FAQ available for informational purposes only and we always recommend working with qualified and local legal counsel when structuring fiscal sponsorship relationships.

Is Fiscal Sponsorship a Service Provided for a Fee? Why it isn’t and why it matters. By Erin Bradrick and Josh Sattely

Fiscal sponsorship is a growing part of the nonprofit sector and, when done well, is an important and impactful tool for furthering public benefitting work and activities. However, because fiscal sponsorship is not a relationship that is explicitly defined anywhere in the law or Internal Revenue Code and is instead most often defined in a written contract, we see fiscal sponsors using a wide range of words and phrases to refer to what are essentially the same things. For example, comprehensive (or Model A) fiscal sponsors might refer to the projects they sponsor as “affiliates”, “partners”, “allies”, “projects”, or “clients”. As the field of fiscal sponsorship continues to grow and to attract additional attention from charity regulators and other governmental agencies, we believe there’s a strong case for developing a common vocabulary of key fiscal sponsorship terms, starting with how we refer to the amounts that fiscal sponsors allocate to cover their operating expenses. We won’t provide an overview of the basics of fiscal sponsorship here, but you can find more information here, here, and here.

Regardless of the model of fiscal sponsorship offered, fiscal sponsors of course incur costs and expenses in offering fiscal sponsorship, including in the form of staff time, administrative support, bookkeeping and accounting, reporting and other compliance, insurance, and other areas of overhead. In order to cover such costs, many fiscal sponsors allocate a portion of the funds received for the purposes of a sponsored project (often a specified percentage) to support shared operations costs. While this amount is commonly referred to as a “fiscal sponsorship fee”, we would like to encourage fiscal sponsors to instead consider referring to it as a “cost sharing”. Hear us out.

We (Erin Bradrick on behalf of the NEO Law Group and Josh Sattely for Social Impact Commons) had the privilege of attending the 2022 National Network of Fiscal Sponsors’ conference in sunny San Diego. In addition to great peer learning and networking, we had a chance to talk vocabulary and found that many fiscal sponsors are still referring - in their fiscal sponsorship agreements, on their websites, and in conversations - to the groups they sponsor as their “clients” that are charged a “fee for services”, while others had shifted to referring to “projects” and “cost allocations”. Fundamentally, what’s being provided by fiscal sponsors and how it is paid for is the same within the various models of fiscal sponsorship, so why the different language? You may think this a question of semantics only of interest to academics and overly caffeinated exempt law attorneys, but there are real implications and potential consequences for how these relationships and cost structures are characterized.

The language used to describe how a fiscal sponsor organization covers its indirect and overhead costs is important, and we encourage sponsors to move away from the “fee for service” characterization for three primary reasons:

It’s not legally accurate. At a basic level, comprehensive (or Model A) fiscal sponsorship is simply a nonprofit carrying out charitable programs. It’s how the programs are carried out - namely by pushing as much managerial and strategic decision making as possible to the program level and having an agreement memorialize the relationship that generally gives a third-party the right to request a spin out of the project - that makes it fiscal sponsorship. Just as a nonprofit would not call an internal program a “client” and charge it a “fee”, neither is it appropriate to frame Model A relationships in that manner. Likewise, pre-approved grant relationship (or Model C) fiscal sponsorship is essentially a grantor-grantee relationship. You don’t see foundations referencing a “fee” they charge to engage in grantmaking and neither should fiscal sponsors. In either model, there’s rarely, if ever, a third-party paying the fiscal sponsor a “fee” for fiscal sponsorship services – rather, the fiscal sponsor is receiving purpose-restricted funds and using a portion to contribute towards covering its general administrative and operating expenses.

Language signals values and intentions. For fiscal sponsors striving to build deep relationships steeped in trust and reciprocity, referring to sponsored projects as “clients” and charging them a “fee” is not only inaccurate from a legal standpoint, it may send signals that counter the messages and intentions a fiscal sponsor is otherwise working so hard to cultivate. Given that fiscal sponsors exercise ultimate oversight responsibility over the activities and use of funds of the organization, including by sponsored projects, when a fiscal sponsor chooses to use “fees” and “services” language, it runs the risk of setting inaccurate expectations about the nature of fiscal sponsorship and the degree of control that the fiscal sponsor is required to maintain and exercise. In our experience, a lack of clear alignment and understanding between fiscal sponsors and projects about what fiscal sponsorship is and what it isn’t is often a significant contributing factor when problems arise in these relationships.

Protecting fiscal sponsorship practitioners and the field calls for accurate messaging. As discussed, referring to sponsored projects paying “fees” implies that fiscal sponsors are providing services to third-parties, which is not accurate. Giving that impression to regulators or the general public perpetuates the inaccurate notion that fiscal sponsorship is a conduit or a “charity-for-hire” mechanism, rather than highlighting the central oversight and support functions that fiscal sponsors play in carrying out compliant and impactful charitable work. Appropriate characterization of the relationship and cost structure protects the organization and helps advance the field.

As the field continues to grow and evolve, consistent use of legally accurate and values-aligned framing will help funders, regulatory agencies, and groups seeking fiscal sponsorship better understand the true nature of these relationships. It may also give staff at fiscal sponsors a grounded understanding of how they contribute.

For this post, we do not offer a single alternative term to express how administrative costs are shared within fiscal sponsor organizations, but examples we’ve seen include “administrative cost allocation”, “overhead cost share”, and “member contribution”. A future post led by our partners in the nonprofit finance and accountancy realm will go deeper into accounting considerations which may inform both what you call and how you report on how these funds flow. But for today, our takeaway message is, if you are a fiscal sponsor, please consider the implications of what language you use to describe your relationships and cost recovery structure. Happy sponsoring!

Possible Futures - A Vision Quest for Fiscal Sponsorship

NOTE TO THE READER

The below draft paper from Social Impact Commons is intended as a companion piece to a field-wide scan of the fiscal sponsorship ecosystem, being undertaken as a collaboration between Social Impact Commons and the National Network of Fiscal Sponsors (NNFS) in the fall of 2022. The field scan will gather basic organizational, diversity and inclusion, and capacity-related data on U.S.-based fiscal sponsors of all sizes and models.

The goal of this paper is to present and continue to shape the case for fiscal sponsorship to accompany the field scan’s data on the size and shape of the fiscal sponsorship ecosystem. These are two different, but complementary elements of the argument for the overall value and impact of our work.

The below text is an opening salvo from Social Impact Commons. In lieu of traditional “peer review” processes, and to incorporate multiple voices in this casemaking effort, we are welcoming input and direct contributions of content to this paper from our community, including but not limited to:

Editorial and commentary

Stories and case studies

Data and analyses

Photos and graphics

Vision statements for the field

The contribution period will be open August 11 and close on or around September 30, 2022, with the intention of issuing a final paper in October or November. All contributions are voluntary and will be credited. The final paper will be released under a Creative Commons license. A pdf of this paper may be accessed here. If you are receiving this paper from another source other than the Social Impact Commons website, please refer to this page for more information on this initiative and how to engage.

*** WORKING DRAFT - v.1 August 11, 2022 ***

Possible Futures - A Vision Quest for Fiscal Sponsorship

PART I: MANIFESTO

The field of fiscal sponsorship stands at the threshold of a new era of growth and transformative potential for the nonprofit sector. This moment has been largely propelled by the growing challenges to civil society and urgent call for social justice in the face of resurgent autocracy and white supremacy, coupled with an accelerating cadence of ecological disaster. In our age of social and environmental justice movement building, it is also likely being fueled by new generations of change leaders that find resource sharing and solidarity-oriented solutions more compelling than going it alone.

Fiscal sponsorship is commonized nonprofit management and infrastructure, or “management commons”. It describes a range of approaches to nonprofit structure and practice aimed at sharing essential operating capacities among multiple aligned missions and visions. As such, fiscal sponsors offer a potential path to permanent and scalable restructuring of our sector around collectivizing management, distributing risk, driving efficiency, and enabling more equitable access to charitable resources.

Yet, we labor under a private-sector worldview that privileges independent nonprofit formation, tax status, and operations as the orthodox “model” and only path to validity and vitality. Independent formation and operation and the “enclosure” (privatization) of assets may make sense for certain business models situated in the for-profit sector. But it is incoherent or unnecessary in the nonprofit sector, whose assets are managed in public trust. As such, nonprofits and the sector as a whole are the closest we come to true commons–resources held in common and managed in a cooperative manner. Fiscal sponsors present both the archetype and entrée into a future of vastly more robust resource sharing.

The American mythology of rugged individualism, inflated by neoliberal capitalism’s worship of self interest still prevails and has left us with the false axiom that independent vision demands independence of infrastructure in the social good sector. Every person or group of people with a charitable vision requires their own nonprofit, staff, tax exemption, operating systems, and so on. As a result, there are roughly 1.5 million nonprofits in the U.S. today, 88% of which operate below $500,000 in annual revenue. Ninety-seven percent of all nonprofits operate below $5 million. And this not even counting the immeasurable “informal” activity of our sector–work happening outside traditional nonprofit structures.

The assumption that independence of nonprofit mission and vision requires independence of formation, exemption, and operation is not only false, it is also fatal to the long-term sustainability and impact of the nonprofit sector. Decades of research on the sector offers a consistent refrain: organizations are financially fragile (but stalwart in spirit!), lack capacity, struggle with developing resources, and so on. These are symptoms of the same underlying affliction: fragmentation brought on by the above false axiom. The result: a vast landscape of (often) intentionally smaller but invaluable stand-alone nonprofit organizations, most of which are not scalable by design or intention. These organizations are most often the ones operating in communities and possessed of trust and cultural competency to deliver effective and responsive services. Unfortunately, they remain under capacity and under-resourced owing to their small scale.

Fiscal sponsors, as collective capacity builders, offer a new vision of hope for the sector. We are risk managers at heart, helping projects navigate risk, failure, and success. We are expert repositioning technicians, designers of efficient systems. We are trusted platforms that can leverage networks, cultural competencies, and relationships at scale. And most of all, we are structures for shifting power to leaders and communities that have long been starved of access. We can be the vanguard of long-overdue change in our sector. It’s no longer an option. It’s urgent and imperative.

What’s at stake? Quite possibly the future of civil society in America and our planet.

Today, 501(c)(3)s represent more than $2 trillion in annual spending and activity–not counting the under-documented and under-compensated labor and in-kind contributions that are the lifeblood of our work. In financial terms, this makes public charities financially equal to about 50% or more of the entire U.S. federal budget, which averages about $4 trillion. Since half of the federal budget is spent on the military, our sector’s investment in social benefit work is arguably equal to if not greater than that of Congress.

The nonprofit sector has always carried the lion’s share of water for social good in this country. But as polarization continues to tear apart the American social fabric, it is also fast becoming the last refuge of civil society and efforts to curb planetary disaster. We are witnessing the erosion of function and legitimacy of our foundational democratic institutions across all three branches of government. A Cold Civil War has yielded social unrest and intractable deadlock in legislative bodies at all levels that everyday threatens the wellbeing of millions of people. While we must continue to fight for the hope of better government and more civil polity, the extreme dysfunction of government and its direct service agencies has made the nonprofit sector the frontline of the battle for social justice and the health of our planet. Government funding for nonprofits remains significant, but where government funding fails, nonprofits can turn to private sources.

We cannot continue with a paradigm that mandates independent nonprofit formation and status as the goal for every social mission. Our reigning strategy, to build the capacity of one organization at a time falters every day in the face of barriers to accessing philanthropic resources and the challenges of moving resources into a fragmented ecosystem. It also feeds a vicious illusion of scarcity–there seems to never be enough money to buy the capacity we need. This may be true if we confine ourselves myopically to the limits of institutional philanthropy as the predicate for social action. But the American nonprofit sector has always relied on the generosity of individuals, which opens a much more vast landscape of potential resources.

In truth, the human will to make and do and, at any given time, our collective drive will always outstrip the resources on hand. This will is the leading force that drives our sector forward. In the perennial chicken-and-egg question of which comes first, financial capital or human drive? It’s always the latter; the former follows but mostly in instances where the doers have the right combination of luck and privilege. What we most urgently need, then, is more ready, equitable, efficient, and sustainable access to the scaffolding needed for people to gather the resources and get to work. Fiscal sponsors are that scaffolding for the nonprofit sector. And with it, we may build and strengthen the edifice of civil society with the care and urgency that the crises of our world demand.

Despite our most selfish predilections, which have been fanned by the fires of late capitalism, humans in general are, at their core, collaborative and compassionate, at least so says evolutionary biology. In the face of adversity, we help others, solve problems, take initiative, and the result is millions of informal acts of social good, happening both between and outside of conventional institutions, and under a surging tide of nonprofit organizations.

To challenge the path of independent nonprofit formation, however, is to challenge a fundamental paradigm–to change the very core of our beliefs from one grounded in the management of bounded privatized assets to one of mutual stewardship of boundless public commons. Make no mistake: to propose such a shift in today’s America is to suggest that the world is flat or that the sun does indeed revolve around the earth.

Fiscal sponsors lead the way for our sector out of this desperate and fragmented land toward greater collective fulfillment of our will to work on the project of civil society. We are the original commons managers, stewarding a multitude of visions in the direction of hope.

PART II: CALL TO ACTION

As the nonprofit sector, our first step down this path is to declare that…

We embrace a world of radical pluralism in which independence of ideas and agency does not require independence of infrastructure. Through the commonized management of fiscal sponsors, everyone with an impulse to bring about positive social change can have access to the infrastructure they need to pursue their vision and flourish, or falter, adjust and continue on. We shed the garb of economic Darwinism imposed by free-market capitalism and recognize that the will to justice and pro-social work in all its diversity is itself a charitable purpose. Fiscal sponsors provide a welcome haven for that purpose.

We move from fragmentation to collectivisation. When regarding the vast landscape of fragmented nonprofits the minds of many move to dystopian visions of placing it all on the cloud (if we ask Silicon Valley) or undertaking a mega-merger of all the small organizations (if we ask Corporate America). There is a more grounded solution that leverages the strength of local communities and the power of local knowledge, leadership, and cultural solidarity: commons management, for which fiscal sponsors already hold the model. What if we moved our fragmented nonprofit community one step toward greater solidarity through regional, field-focused, and identity-driven fiscal sponsors–a commons manager in and for every town, city, and community?

For fiscal sponsors to lead this journey, we must…

Expand the fiscal sponsorship ecosystem. While there is still case making to be done, after sixty years of practice, we enjoy some confidence in our work and future. Our attention needs to be trained on securing long-overdue philanthropic investment, workforce development, innovation, and democratization of the collective knowledge we possess. Fiscal sponsors likely manage less than 5% of the more than $2 trillion activity of the nonprofit sector. There’s ample room to grow, if we muster the courage and organizing capacity.

Shift from a field defined by law and finance to a field more defined by organizing, activism, commoning, and movement building. While the tools and trappings of finance and law are essential to our work, the field of fiscal sponsorship (as with most of today’s institutions) has been largely defined by law and finance. From the beginning we have defined charitable work predominantly by corporate form and tax status. It is no surprise that the only definitive text on fiscal sponsorship is a legal text. At this point, we need to expand our tools and definitions to ground fiscal sponsorship in the practices of organizing, solidarity, and movement building–ensuring not just statutory compliance, but nurturing the social bonds and trust needed to address today’s most pressing problems.

PART III: POSSIBLE FUTURES

We vastly accelerate the forces of solidarity building and social justice. As global challenges facing civil society continue to mount, we are turning to solidarity and movement building. Indeed much of the grassroots leadership around social justice over the last five years has found a welcome haven in fiscal sponsors, which are well positioned to be the backbones for fostering and sustaining greater social equity.

We re-task billions in charitable funds from needlessly duplicated infrastructure directly to front-line work. According to the Urban Institute, the nonprofit sector realized $1.94 trillion in expenditures in 2020. Social Impact Commons has conducted several sample economic studies using the rich nonprofit financial data of Data Arts, looking at about 1,000 organizations operating under $2 million in budget. We compared costs to manage through independent legal formation with the equivalent costs to manage by sharing the same back-end infrastructure fiscal sponsors offer. Under fiscal sponsors, backbone costs were between 10% and 30% lower than those incurred by operating independently–and that’s just a sample and does not even speak to the intrinsic values to nonprofit leaders of receiving such holistic back office support. If we were to collectivize infrastructure across our sector through fiscal sponsors, as suggested above, that could mean a minimal “savings” (re-allocation to programs) of about $200 billion per year–roughly twice the amount of all giving and grantmaking in the U.S. in calendar 2021!

To realize this audacious vision, the fiscal sponsorship field grows and becomes more diversified through expansion to new cities, towns, suburbs, exurbs, and rural communities and through specialization across cultural competencies, identity groups, and field expertise. Instead of nearly 1,000,000 small nonprofits struggling alone in the wilderness, they share core backbone capacity and social solidarity through 10,000 local or specialized fiscal sponsors providing commonized management.

To move from the roughly 1,000 fiscal sponsors operating today to an ecosystem of 10,000, our field becomes understood by philanthropy, policy makers, and nonprofit leaders as no longer a marginalized model, accounting for a fraction of the sector’s activity, but critical infrastructure for the sector, managing a substantial amount of its activity and future growth.

Our field continues its work to relinquish the reins of power to BIPOC and other marginalized communities. It shifts its culture and practices from those that consolidate power and replicate white supremacist models of nonprofit management–the Nonprofit Industrial Complex–to a community of practice that provides more equitable, sustainable, culturally relevant, and impactful nonprofit resources for communities everywhere.

And lastly, fiscal sponsorship sheds its moniker, born of finance and legal coinage, and becomes management commons, transforming its image from a temporary waystation on the weary road to independent nonprofit status to a permanent structuring solution for solidarity and social justice.

This vision is not new. It is as old as our sector. Why does it still seem so elusive? Because we have not yet conjured the fortitude to challenge the ontology of the private sector that holds our sector so thoroughly in its thrall. To suggest that the proliferation of the independent charitable form is not only unnecessary, but perhaps the greatest thing holding our sector back from true flourishing, still draws looks of quizzical unease.

It took well over a century for Nicolaus Copernicus’s heliocentric model of the universe to be accepted by the powers to be, religious and secular. We hope for the sake of our people and the planet that we don’t take as long to lean into the work of shifting our ontology for the social good sector. If we are to salvage centuries of progress toward a more civil society, currently under threat, and rescue our planet home, time is not a luxury we possess.

PART IV: FROM MYTHS TO MANIFESTATION

NOTE: In this section, we are inviting expansion through commentary, case studies, research, analysis, and vision statements that challenge the below myths and explore and amplify the case for fiscal sponsorship. Initially, we are organizing this around four topic areas and myths that persist about fiscal sponsorship related to each one: Scale, Efficiency, Justice, and Sustainability. We have started the thread in each case with a few myths, but welcome others. In each section we have started the ball rolling with some preliminary text, to be expanded over the coming weeks.

Essential to realizing the actions and vision outlined above is moving from myth to manifestation through challenging and illuminating a number of frequent misperceptions and misunderstandings about the fiscal sponsorship field. In this section, we focus on four major areas of conversation, Scale, Efficiency Justice, and Sustainability and have invited voices from the field to expand and fill in the contours of these subjects.

SCALE - of or pertaining to the ability of fiscal sponsors to support the scaling of sponsored projects, their fiscal sponsor resources, to the field of fiscal sponsorship itself. We hear…

Fiscal sponsors are only incubators and accelerators to help organizations on the way to independent formation and exemption. We know that fiscal sponsors, in particular “Model A” comprehensive sponsors, are increasingly seen as the forever homes for the projects they sponsor. We work with fiscally sponsored projects benefiting from decades long fiscal sponsorship relationships. Given their size and focus, eventual independent status is entirely illogical. While the incubator and accelerator functions will always be a value of fiscal sponsorship, it may become a minority case in the future.

The path to scale for fiscal sponsorship is only scaling the established sponsors; building new fiscal sponsor infrastructure is too hard/expensive. We hear frequently about the challenges fiscal sponsors have in garnering direct philanthropic support to build capacity. Funders often feel it’s an easier path to invest in large, established sponsors, instead of going through the effort and cost of starting a new one. This is a path, but we can’t ignore the forces of field specialization as well as diversity in cultural competency and community building that more recent generations of fiscal sponsors represent.

Fiscal sponsors cannot support projects once they hit a certain budget or operating scale. We hear this often–usually with arbitrary assumptions about the size of the budget that would inspire spin out. In fact, many large sponsors support projects that exceed $5 million in budget–projects that would otherwise be in the highest percentile of budget size for nonprofits overall. The economics of fiscal sponsorship, assuming appropriate sponsor capacity, can work at virtually any scale.

EFFICIENCY - Of or pertaining to the cost of fiscal sponsors and their classification as nonprofit intermediaries and the kinds/nature of support they provide. We hear…

Fiscal sponsors add unnecessary cost and inefficiency to the work of the sector; sponsor fees are too high. We know that study in recent years of nonprofit overhead has led to the debunking of the pernicious sense that nonprofits ideally should have zero overhead. The “Overhead Myth” has proven that some kinds of missions register more than 50% in so-called overhead, and that “indirect cost”, as we’ve always known, is a relative and highly variable notion, depending on the resource model of the nonprofit. As mentioned earlier, our own studies using the rich DataArts database of IRS Form 990 data, has evidenced upward of 10% “savings” in costs for organizations operating under a comprehensive fiscal sponsors, as opposed to going it alone.

Related to concerns over cost, are assumptions that administrative time and process threatens to bog down the work of sponsored projects. This can be the result of poor management or lack of capacity at the sponsor, but it is more often the result of the management capacity that fiscal sponsors provide to projects where in many cases there had been none. Filling a management deficit can easily seem like an imposition, but expediency of action needs to be balanced with good and consistent stewardship and management practices.

Fiscal sponsors are only purveyors of back office support and nonprofit compliance. The perception that fiscal sponsors are just transactional providers of finance, HR, and compliance support persists. While fiscal sponsors do this work, the range and depth of services offered is expanding to include everything from advancement support, to constituent management, coaching, and other capacity building. In fact, we argue that sponsors are less intermediaries, and more collective capacity builders–common management platforms where almost any management capacity may be developed and shared for greater sustainability. Indeed, the persistence of the core “back office” as the fiscal sponsor staple may largely be tied to the sense that sponsors are only temporary stations on the road to independent status. Why would you want to add more shared capacity, when the goal is to break away? If we shift our thinking to fiscal sponsors as permanent shared management and collective capacity, we open the possibility of developing capacities such as fund development and advocacy at scale for our sector that have long eluded philanthropic solutions.

JUSTICE - Of or pertaining to the ways in which fiscal sponsors diversity, equity, access, and inclusion within the nonprofit sector. We hear…

Fiscal sponsors perpetuate the Nonprofit Industrial Complex. There is a well-founded refrain that fiscal sponsors may deliver economies of scale and efficiency, but are just replicating white-supremacist models of management. This is true, but increasingly, sponsors–in particular those truly embracing a DEIA work or with BIPOC leadership–are able to leverage cultural competency, values, and established trust with their communities. They are building intentional communities around common values and identities. They also manage and distribute risk collectively, allowing people who often cannot otherwise afford the risk (financially or socially) to experiment, learn, iterate, and hold ambiguity.

Fiscal sponsorship is not values aligned with the Solidarity Economy. We hear that fiscal sponsors ask visionary leaders to relinquish agency, autonomy, and power. And fiscal sponsors are often myopically judged, along with the nonprofit sector, as an antiquated infrastructure for social change, to be replaced by more cooperative Solidarity Economy solutions. But in fact, fiscal sponsors can and do engage in Solidarity Economy approaches, centering constituent-governance, mutuality, and power sharing in their relationships with projects. The percent allocation-based cost recovery approach that fiscal sponsors use, allows sponsors to offer low financial barriers to nonprofit expertise and infrastructure. And cost is also proportionate to need.

SUSTAINABILITY - Of or pertaining to the financial, staffing, legal, or structural sustainability of fiscal sponsors. We hear…

Fiscal sponsor business models are not sustainable. Since we only report the planes that don’t land, there remains a perception, in particular in the funding community, that the fiscal sponsorship “business model” doesn’t work. In truth, fiscal sponsor resource models resemble closely those of co-ops: there is a shared management resource and multiple organizations (projects) pay their portion of the carrying cost. Within that basic idea, there is a spectrum of revenue models, all of which are sustainable so long as they are intentional and mindful of their driving values, maintain a balanced portfolio (specific to their model), and responsive to surrounding economic conditions. Sponsors range from 100% cost recovery models (mostly “Model A”) to 100% subsidized models, and everything in between. That said, fiscal sponsors have the same capacity challenges that any nonprofit encounters; they struggle to secure capital from philanthropy to build their shared resources.

Fiscal sponsors are exotic and untested models. Fiscal sponsors are not novel nonprofit structures or practices, but rather the codification and expansion of long-standing nonprofit models. In many ways, a fiscal sponsor is no different than a large nonprofit for multiple distinct programs. Only with the latter, the program likely has less day-to-day management autonomy, needs to cleave to the brand and identity of the main organization, and usually doesn’t have the authority to leave or “spin out”. With the myth of existicism also comes over-concerns about fiscal sponsors and legal and tax compliance issues. To fund a sponsored project is not giving money to a non-tax-exempt entity; in all cases fiscal sponsorship entails making a grant or gift directly to a public charity. And the compliance needs and issues related to both funder and project are no different than with any other nonprofit.

The Real Work of Collaboration & Sharing: What Fiscal Sponsors Can Learn from the Behavioral Sciences

On March 24, 2022, we were grateful to welcome Syon Bhanot to our Member Conversation to discuss the potential applications of research from the applied behavioral sciences field to some of the most persistent problems faced by fiscal sponsors. Syon is a leading scholar of applied behavioral economics, teaching at Swarthmore College, but also a member of a number of research groups, including the MIT Applied Cooperation Team and his own burgeoning practice as a consultant in the study and application of applied behavioral economics. Other leaders in the applied behavioral sciences include these folx and in the popular press, the likes of Richard Thaler, Cass Sunstein, Daniel Kahneman, and others.

The behavioral sciences hold tremendous untapped potential to inform transformative solutions for fiscal sponsorship. This area of study is concerned with how real people behave in real situations, with all of our manifest imperfections. The behavioral sciences field was founded nearly 60 years ago in direct critique and opposition to classical economics, which still dominates a great deal of thinking in the field. The classical school is grounded in an idealized view of human beings as rational optimizers in all cases. If such were true, we would be more able to resist that late-night piece of chocolate cake, or more tragically, we would not have experienced the raging bonfire of moral hazard that led to the 2008 subprime mortgage crash.

Regardless of your model or philosophy for fiscal sponsorship, we are all in the business of sharing resources and infrastructure with our projects. We also rely on the cooperation of our project directors and their teams to work with our sponsor staff in a true co-management relationship. Creating cultures of mutuality, accountability, and sustained cooperation are essential to our work. More broadly, you could argue that the entire nonprofit sector is dedicated, in one way or another, to nudging people to overcome their lesser angels and behave more generously, or “prosocially” toward each other, rather than indulging in pure self-interest. You might also argue that our sector exists, at its core, to mitigate the negative impacts that result from our failure to resist those lesser angels: prejudice, racism, and the extractive, exploitative, and inequitable dynamics of neoliberal capitalism, to name a few.

The question of how we encourage “better” (more prosocial) decisions and actions is a core enterprise of the behavioral sciences. But doesn’t that sound like mind control? And who decides what is a “better” decision? Well, this work is also not to be undertaken without a great deal of thought and consideration as to when and how you apply its ideas. In fact, there is a whole field of ethics that has arisen to address the moral implications of behavioral science.

Syon shared with us a few of the concepts that are studied in his field and that underpin a great number of applications, from government to the private sector, and hopefully with greater embrace, the nonprofit sector as well. Below are some reflections on those concepts and how they might apply to our everyday work as fiscal sponsors.

Repeat Interaction & Reciprocity

There are many studies around the positive/reinforcing effects of repeated interaction as a motivator of behavior, as well as the power of reciprocity, a deep-seated way in which humans relate to each other. While our field talks a lot about mutuality and “community,” many sponsors still maintain very transactional relationships with their projects/sponsees and then wonder why they are treated merely like a vendor of services. There’s nothing wrong with that approach, but if you are preaching a culture of intentional community and mutuality and then work and operate transactionally, some dissonance may result and lead to behaviors you don’t want. Greater degrees of mutuality help build trust, which may allow sponsors to weather bumps in the road more readily as a community.

What might happen if you framed your sponsor-project relationship as much around what the project is bringing to your community as what you are doing for the project–from the moment of application and discernment, through the relationship?

Do you offer opportunities to have your projects support your work as a sponsor through services they have to offer? Do projects get financial or other consideration for such reciprocal support? How else do you engage in intentional reciprocity?

Social Proof & Observability

Another major motivator of behavior (good, bad, and ugly) is social (“peer”) pressure, as we well know. Key to leveraging social proof (or the fact that a significant number of people are doing or are interested in a particular thing) is observability–the ability for people to observe behaviors, register preponderance, and adjust their behavior accordingly. Social media provides a platform for social observability at massive scale and accelerated velocity. The behavioral science wing of the U.K. government conducted an experiment for the British taxing authority several decades back aimed at trying to get delinquent taxpayers to pay. They sent a range of collection letters out with a variety of messages from the expected punitive “or else” letters, to various incentives - but the most effective message in motivating folx to pay up was: “Nine out of ten people in the U.K. pay their tax on time… and you are one of the few who hasn’t paid yet.” The desired behavior became observable – and the deviant behavior was highlighted.

How much of your management behavior is focused on mere reminders and penalty-based incentives to motivate actions: submitting time sheets, reimbursables, and others?

How often do you hold up in very visible (communications) form the number of projects that DO submit on time, for example?

Are there other ways in which you could use social proof and observability to nudge projects toward certain behaviors (or vice versa)?

The IKEA Effect & Sunk Cost Fallacy

The IKEA Effect is so named for the fact that we tend to value something more that we build ourselves. This applies as much to nonprofit organizations, programs, processes, and policies, as it does to pieces of affordable furniture. Closely related to this syndrome is the Sunk Cost Fallacy, which describes the escalation of commitment we enter into when we throw good resources after bad in the hopes of finally seeing the efforts we’ve put into something finally come to fruition. While sustained investment is often needed to realize a successful program, we also need to be mindful not to become the gambler who keeps on losing in the hopes of recouping losses with the next hand. Both of these behavioral attributes lead to reticence to end ineffective programs, substantially re-think our models, or undertake any significant change for that matter.

These dynamics are also particularly prevalent in founder cultures, which constitute a vast quantity of fiscally sponsored projects, and may be the reason that culture or behavioral shifts in founder-led projects are often difficult to undertake–especially the decision to wind down, if a project has served its purpose or becomes unsustainable. For-profit start-up cultures tend to valorize and celebrate “exit” as a badge of achievement. But in the nonprofit sector, we tend to think of exit in negative terms, even as a moment of failure. The behavioral sciences also have studied how we register loss more acutely than gain (aka “loss aversion”), so both the IKEA Effect, loss aversion, and the Sunk Cost Fallacy can conspire to create unhealthy founding dynamics.

How can we create space to speak more frankly about these dynamics, embrace change and transition/succession, and celebrate exit as a moment of success for projects and sponsors alike?

How might sponsors harness the IKEA Effect positively, as a means of strengthening social ties within a community of projects through fostering a sense of ownership and participation in the design and development of sponsor resources?

Overconfidence

Lastly, we discussed our tendencies to be overconfident in our estimation of many capacities and abilities, which has been well studied and demonstrated by the behavioral sciences. For example, this may lead to organizations under-estimating their capacity to support a new project coming into our portfolio, especially if it is of significant size and complexity. Saying no is never an easy thing, and our empathic desire to extend a helping hand, coupled with some manner of overconfidence can find us over our head quickly.

We may not just overestimate our organization’s capacity to manage and operate, in our drive to achieve greater social justice we likely often overestimate our ability to understand the cultural contexts of the leaders we support. Even with the growing discourse around equity and inclusion, implicit bias training and awareness building, we also need to take care that mere awareness doesn’t lead to overconfidence in our ability to overcome such biases. Such work will never be finished.

How might we provide space and support for our staff and project teams, allowing them to celebrate the impact they have on some of the world’s most intractable problems, while acknowledging the limits of our agency. Practicing humility without helplessness requires intentional space for mindfulness, conversation, and healing for sponsors and projects alike.

And how might we engage in sharper portfolio management and other, more regular, organizational health assessments to support more intentional conversations around operating capacity limitations and strategic growth?

The above are just a few ideas from the vast field of the behavioral sciences. We encourage our peers and colleagues to delve deeper into this exciting area of research. It may just hold clarity about and answers for some of the most perplexing questions our field faces.

To continue your exploration of the behavioral sciences, visit Syon’s personal page with links to peer resources.

The Common Impact Initiative: The Case for Field Research

The field of fiscal sponsorship is growing by leaps and bounds, driven by the diversity of urgent overlapping problems and opportunities for reinvention that we face today: social justice, climate change, income inequality, and many others—not to mention the global COVID-19 pandemic. Adding to these broader forces are the changing dynamics of the nonprofit sector writ large. Fiscal sponsorship is finding itself at the center of the conversation around nonprofit resource sharing, consolidation, and general “repositioning”. And new generations of social entrepreneurs and changemakers are finding fiscal sponsorship an attractive and flexible alternative to forming standalone nonprofits. We are sorely overdue for current and more comprehensive data on this dynamic and impactful field.

The Opportunity

The field of fiscal sponsorship is growing by leaps and bounds, driven by the diversity of urgent overlapping problems and opportunities for reinvention that we face today: social justice, climate change, income inequality, and many others—not to mention the global COVID-19 pandemic. Adding to these broader forces are the changing dynamics of the nonprofit sector writ large. Fiscal sponsorship is finding itself at the center of the conversation around nonprofit resource sharing, consolidation, and general “repositioning”. And new generations of social entrepreneurs and changemakers are finding fiscal sponsorship an attractive and flexible alternative to forming standalone nonprofits.

These dynamics are motivating the need for a deeper understanding of the depth and breadth of the field today. Philanthropies and policy makers are asking for information on the size and shape of the ecosystem. Amidst the sector’s wider focus on impact, how or to what degree do fiscal sponsors define impact, and do we measure it? Finally, we know that the breadth of fiscal sponsorship practice extends far beyond the bounds of self-identifying fiscal sponsors to include organizations engaged in sponsorship, intentionally and accidentally, as well as fiscal-sponsorship-adjacent work that shares common practices and concerns, but carried out by nonprofits not identifying as fiscal sponsors. These include large, multiunit nonprofits and networks, found often in healthcare and higher education, as well as multi-entity structures commonly found among community land trusts and nonprofit development corporations.

Of the many virtues and values that fiscal sponsorship offers, two areas of interest and opportunity rise to the top today: Equity/Access and Efficiency/Sustainability. Anecdotal evidence abounds and some quantitative data exists illuminating various aspects of how sharing resources can lead to greater sustainability, mission focus, and economies of scale, as well as provide improved and more equitable access to nonprofit resources. But we are still lacking in field-wide, collective data on these fronts, which is predicated on our ability to identify some key data points for each that can be tracked across a diverse ecosystem of sponsors.

Equity & Access: Fiscal sponsors offer ready-at-hand, “plug and play” infrastructure for leaders of new, grassroots, and community-based projects, virtually eliminating the prevalent knowledge, legal, and financial barriers to starting a nonprofit . This attribute of fiscal sponsorship alone presents a solution for many of the access and equity challenges that face BIPOC and other marginalized leaders in accessing the resources of the tax-exempt sector and advancing the interests of their communities. Indeed, many of the first fiscal sponsors were formed in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement out of the need to provide communities of color greater access to government funding streams. Effective fiscal sponsors share their resources through equitable sharing power and authority with the leaders of the projects they serve. Yet, the fiscal sponsorship field remains largely white-led, reflecting the larger profile of the nonprofit sector. Fostering the development of more fiscal sponsors of, by, and for historically marginalized communities is of urgent importance in the larger struggle for racial equity and social justice. Fiscal sponsors can be a catalyst for transforming the nonprofit sector from its role as participant in racial and social inequity to that of agent in uplifting leaders and communities that have been long disenfranchised.

Efficiency & Sustainability: Fiscal sponsors are collective capacity builders. As fiscal sponsors add more projects and grow their shared support, the overall capacity of the community of projects grows as well, a much more efficient way to build capacity than one organization at a time. Using data from SMU Data Arts, Impact Commons conducted a comparative study of a sample of 475 arts organizations operating below $2 million in budget in Southeastern Pennsylvania. We found that they spent between 17% and 27% of revenues on the equivalent back office supports that a comprehensive fiscal sponsor can provide for between 10% and 15% of revenue. That is a “savings” difference or re-allocation to program or other priorities of about 10%.

In addition to financial economies, we also find that a number of fiscal sponsors provide a wide range of wrap-around consulting services, as well as community learning and collaboration. As collective capacity builders, they are also collective risk managers. The cooperative nature of the fiscal sponsorship business model--typically a percent of each dollar received is allocated to shared expenses--means projects are only paying for services when money comes in, allowing them to weather vagaries in cash flow and other events through the collective strength of the portfolio of projects. This ultimately leads to greater overall sustainability of the community. Even in the event of a catastrophic event, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, a fiscal sponsor is able to mobilize stabilizing resources and support more quickly for its projects, than if they were operating independently.

Over the past year, we have heard from many fiscal sponsors that COVID led to a great upswing in demand for support from new projects, as well as dramatically increased revenues for many existing projects. This precipitous growth motivated strategic planning, self-assessment, and an urgent need to evaluate the question of “right size”. How big do we want to be? If we want (or need) to grow, how do we do it responsibly? The need for working capital and change capital for sponsors (and their projects) is greater than ever, elevating the urgency for field-level case making to philanthropy.

The Status

Fiscal sponsorship has been around since 1959, when TSNE MissionsWorks launched the first recognized “Model A” comprehensive fiscal sponsorship practice. The first (and still only) authoritative text on the field appeared in 1993 by attorney Gregory Colvin, Fiscal Sponsorship: Six Ways to Do It Right, and has since gone through several reprints. In 2004, the National Network of Fiscal Sponsors (NNFS) was formed as the field’s first trade group, with support from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. Fiscal sponsorship operates within the bounds of charitable and tax law, but has remained relatively untested in case law.

Today, the San Francisco Study Center (fiscalsponsorshipdirectory.org) tracks about 300 fiscal sponsors. This is complemented by the membership rolls of NNFS (fiscalsponsors.org), which number about the same, though the degree of overlap in these databases is unknown. Beyond the self-selected groups in the above two databases, anecdotal evidence from funders and nonprofit leaders indicates, as mentioned above, that there are many informal or occasional fiscal sponsors: nonprofits that provide fiscal sponsorship support when the need arises, often not as a publicly advertised service or significant component of their mission.

Over the past year, the lack of shared impact data for the field, as well as census-level data describing the shape and size of the fiscal sponsorship ecosystem has revealed itself to be a significant barrier to our work, as well as the growth of the field. For example, lack of baseline data limits the ability to find fiscal sponsor matches, refer sponsees from one fiscal sponsor to another as well as better understand different approaches to shared services and how an organization can benefit from them. Moreover, there is still a dearth of awareness in the sector and among nonprofit leaders of the potential and breadth of support and impact that sponsors can offer. Members of the funding community certainly see the potential fiscal sponsorship holds and are investing in sponsor creation and capacity building. Yet, as a whole, the philanthropic sector seems to be stymied by a lack of evidence about the size and the impact of the fiscal sponsorship overall.

The first and last field scan for fiscal sponsorship was commissioned in 2006 by Tides, following a 2005 study by TSNE MissionWorks of funder attitudes toward fiscal sponsorship. With the increased national reckoning with racism and social injustice, three studies have been commissioned examining equity-oriented practices in fiscal sponsorship and intermediaries in general: Centering Equity in Intermediary Relationships (Change Elemental, 2019), commissioned by Ford Foundation; Reimagining Fiscal Sponsorship in Service of Equity (TSNE MissionWorks, 2021); and most recently, Leveraging Fiscal Sponsorship for Equity (PROVOC & New Venture Fund, 2021, forthcoming). Building on these studies, which were more focused on patterns of practice, we now need to map the landscape to strengthen the case for fiscal sponsorship, as well as identify opportunities for strategic growth.

Big Questions

The field is at an exciting point of inflection after 60 years of practice, and more information is needed to effectively navigate the path forward. The below three foundational questions loom large on the landscape.

How is the field described, what are its defining attributes, and how big is it?

Can we define patterns (shared thinking) around the impact that a fiscal sponsor has on their projects (sponsees), such that patterns of common impact may be established for the field?

Does fiscal sponsorship offer a more equitable, scalable, sustainable, and impactful path for nonprofit work than the traditional, fully independent nonprofit route?

To begin to delve into these questions, Social Impact Commons is organizing a multi-year Common Impact Initiative, a collaboration among a consortium of convening, data holding, and supporting organizations for the fiscal sponsorship community. Our first step will be to assemble this group to gather some baseline data from known (self-identified) fiscal sponsors reachable through the networks of the consortium. Before the end of 2021, keep an eye out for a survey instrument. If you are a fiscal sponsor reading this post, we hope you will participate.

Here’s to the road ahead!

Equitable Contracting - Patterns of Practice

Commoning places a strong value on decentralized or shared power structures and relationships as one of the essential paths to equity and justice. Contracts and agreements of all kinds, but in particular between sponsors and projects, should be approached through the lens of mutuality and shared authority and responsibility. Below are equitable contracting design principles--patterns of practice--we have identified as considerations when constructing, negotiating, and entering into contracts.

Commoning places a strong value on decentralized or shared power structures and relationships as one of the essential paths to equity and justice. Contracts and agreements of all kinds, but in particular between sponsors and projects, should be approached through the lens of mutuality and shared authority and responsibility. Below are equitable contracting design principles--patterns of practice--we have identified as considerations when constructing, negotiating, and entering into contracts.

Table Setting. It is helpful to provide context around the missions and purposes of the parties and their intentions surrounding the engagement. We use recitals or background statements at the outset of the contract to communicate this important information.

Smartly Organized. Well-written contracts can serve as handy reference guides to help understand and manage relationships. One should not have to sift through page after page of “legalese” to find the terms most frequently referenced by staff. The terms of a contract should be organized in a way to promote ease of use and we suggest separating the legal “boilerplate” language from the terms that matter most to stakeholders which are placed in an exhibit or at the beginning of the contract. These terms include the key timelines and milestones, designated contacts, description of who is doing what (i.e. the “scope”), and how and when money and/or other resources are exchanged. When the parties anticipate they may enter into a series of engagements over time, use a “master service agreement” where the parties agree to the general legal terms that will govern their overall relationships at the outset and then each time they wish to enter into a special engagement with one another, a simple sheet listing the key business terms is signed and becomes a part of the larger agreement.

Use Definitions. If the contract will have words or phrases carrying special meaning used in multiple parts of the contract, add a definition section so there is a simple reference sheet that makes very clear what all of these terms mean. Capitalize those words or phases when they appear in the contract so the reader understands they are associated with the special meaning from the definition section.

Fair Terms. Contracts should not be one-sided but rather have balanced key clauses including the following:

Notification. In general, each party should have a reasonable time to respond to concerns raised by the other party and an equitable process should be in place to address concerns. Sanctions and penalties, if any, should be graduated so as not to impose the maximum penalty on the first offense.

Indemnification. Each party should be responsible for its own actions and the maximum liability they can be exposed to should be in proportion to their responsibilities and the amount of funds being exchanged.

Disputes. When conflicts can’t be resolved between the parties, an independent mediator should be utilized before escalating to any litigation process. Consider power dynamics and resources needed to travel and participate in any conflict resolution process when deciding on the venue for arbitrating or litigating conflicts.

Intellectual Property. When it comes to intellectual property such as copyrights, predominant and historical corporate thinking says the party paying should own the work product or have the exclusive right to use it for certain purposes. This “winner takes all” mindset is evolving for nonprofits and for-profits alike and it is worth considering opportunities to share ownership among the parties or making the work freely available to other stakeholders using licencing constructs such as Creative Commons or open source. Additionally, funding sources increasingly require their grantees share work produced with their grant funds with the general public; something to keep in mind.

Gender Neutral. Contract language should be gender neutral referring to person or individual rather than assigning sex or sentences should be structured to eliminate pronouns completely. Also, when names of individuals are used, list them in alphabetical order.

Plain Language: Phrases like “Notwithstanding the aforementioned” and “the party of the first part renders unto the party of the second part” add nothing beyond confusion and frustration to a contract. Legal drafting should employ short sentences, clear language, avoiding complex construction, and legal jargon, such as Latin terminology, and abbreviations. Contract sections and headers should be descriptive in terms understandable to an average person. Agreements should be available in the predominant language of all parties, even when United States law is in force.

Risk Appropriate Complexity. The complexity and length of agreements should be appropriate to the risk and relationship that the agreement is meant to govern, with the intention for agreements to be minimal in length and not “over-manage” from a legal standpoint.

Clear Amendment & Equitable Exit. The manner in which the agreement may be changed or exited by either party should be clearly stated. And if exit or termination is the goal or possible eventuality, fair and balanced (not punitive) terms for all parties should be articulated.

Practical Compliance. Compliance-related matters should be as simple to satisfy as possible, while serving the underlying purpose of the agreement--”over-compliance” should be avoided, or cumbersome compliance standards or methods, where simpler approaches would suffice.

Values-aligned Subcontracting: In agreements where either party is permitted to engage subcontractors, there should be requirements that subcontractors comport with standards of fairness and sustainability in their business operations.

Use of Attorneys. Groups making good use of this guidance and our Commons Tools Library should require less legal expertise as resulting contract structures and terms will be fairer and easier to understand than most contracts. However, contract attorneys can still play an important role in thinking through and drafting solutions to complicated scenarios. When using attorneys to negotiate and/or draft contracts for you, we encourage you to share this sheet to ground them in our shared approach. If legal counsel has questions or suggestions to improve this guidance, we welcome the opportunity to engage.

DISCLAIMER

The above blog post does not constitute legal advice. Social Impact Commons is making these ideas available for informational purposes only. Different circumstances and legal jurisdictions may call for different contract language and we recommend you seek the advice of local counsel in drafting any contractual agreements.

The Right Size - Questions of Growth & Scale for Fiscal Sponsors and Projects

The subject of strategic growth and scale has become a central question for the fiscal sponsorship community. The forces of growing social, racial, and economic inequity in our country, compounded by the pandemic, have fueled both a rush of beleaguered organizations seeking refuge and safety in numbers, as well as accelerated growth in grassroots, social justice organizations seeking fiscal sponsors to accelerate their missions. Most fiscal sponsors are reporting tremendous growth in the demand for their support, and many individual projects are experiencing rapid and significant influxes of support and parallel increases in demand for their services. Questions about how to think about scale, whether to scale, and how big is big enough are top of mind.

The subject of strategic growth and scale has become a central question for the fiscal sponsorship community. The forces of growing social, racial, and economic inequity in our country, compounded by the pandemic, have fueled both a rush of beleaguered organizations seeking refuge and safety in numbers, as well as accelerated growth in grassroots, social justice organizations seeking fiscal sponsors to accelerate their missions. Most fiscal sponsors are reporting tremendous growth in the demand for their support, and many individual projects are experiencing rapid and significant influxes of support and parallel increases in demand for their services. Questions about how to think about scale, whether to scale, and how big is big enough are top of mind.

The distinctly American obsession with bigger-is-better and growth-for-growth's-sake is deeply ingrained in our cultural values and has profoundly distorted our assumptions about the nonprofit sector, largely in unhealthy ways. The assumed value of bigness permeates manifestations, from the “Big Mac” to the spurious free-market mantra, “if you’re not growing, you’re dying.” Growth, accumulation, and scale are so deeply ingrained in American, capitalist culture that to deny their alleged “truth” is akin to asserting the earth is flat.

Today, more than ever, we must challenge bigger-is-better as our reigning paradigm and think about the value of scale and impact in a more multifaceted way, celebrating the value of both big and small and all things in between. For the private sector, growth and scale are mostly driven by market dynamics: the need for dominant (or some specific) market share, competitive advantage, and ultimately, profit. And with profit as the primary motive, scale, success, and value are naturally measured in money.

In contrast, the nonprofit sector, true to its name, is not motivated by profit (or money), but the fulfillment of charitable purpose, or mission. Yet, the growth-for-growth's-sake paradigm and the tendency to assess scale and value using the myopic measure of money prevails--a morbid condition induced upon the nonprofit community through private sector operating assumptions and values. When nonprofit leaders describe their organizations, the first thing out of their mouths is often a statement about the size of their budget. And I’ve found that most fiscal sponsors, when asked the same question, respond with the number of projects “under management” and cash throughput. But is that really why we’re doing this? And do those stats say anything substantive ultimately about impact or mission fulfillment? Not really.

For single-mission nonprofits, the question of scale is often tied to capacity building. Despite the fact that most of our sector is “small” in budget scale, the march to “professionalize” the sector over the past fifty years has forced nonprofits to scale for the sake of attaining a size that can support independent back-office and other infrastructure. (“If we were only bigger/had more money, we could afford a fundraiser, full-time accountant, etc.”) This brand of capacity building continues to be pushed by funders and the management consulting industry, often leading organizations to carry or strive for scale they cannot sustain, all in the name of being big enough to keep standing on their own. Of course, fiscal sponsors offer a solution to this problem: organizations can achieve a right size relative to their mission--even if that means at a modest budget size--while accessing full-charge, but fractional back-office supports.

If we are to move away from growth-for-growth’s-sake and growth-for-capacity’s-sake, whether we represent a fiscal sponsor or a project, we must ask the question, what is the right size for my mission? For fiscal sponsors and the nonprofit projects they support, the answer is complex. In our view, there are four considerable dimensions that inform strategic thinking about scale and impact for fiscal sponsors and their projects.

A Right Sizing Rubric

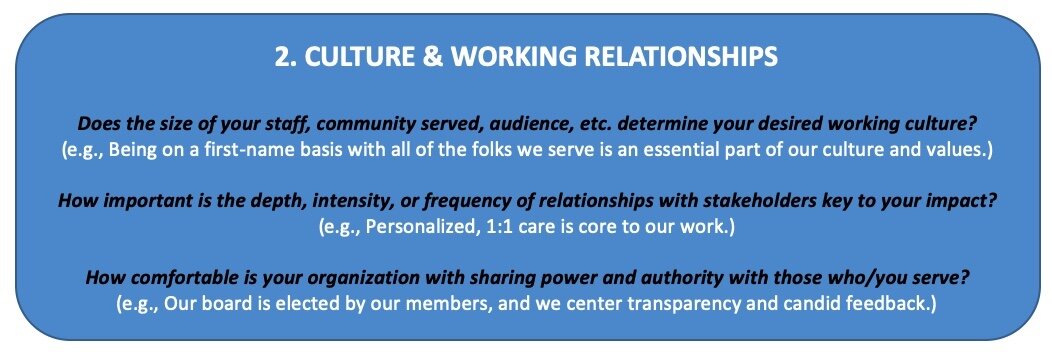

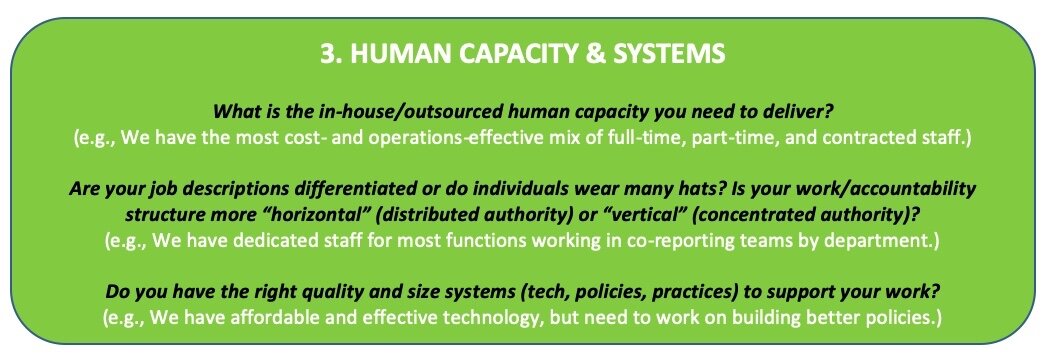

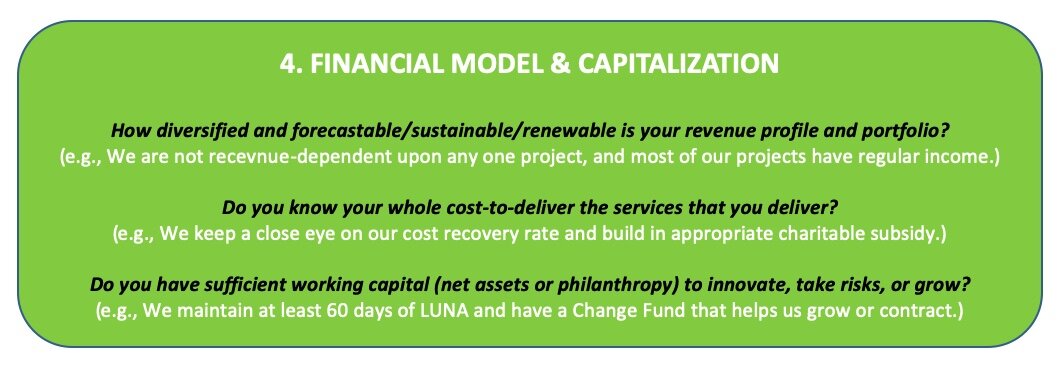

Our proposed Right Sizing Rubric may be used to think about scale for any nonprofit mission. But we share it here as a tool for analysis and consideration of scale for fiscal sponsors and their projects. The below rubric dimensions are relational: Impact & Mission Model relate directly to Culture & Working Relationships, and Financial Model & Capitalization relate directly to Human Capacity & Systems. Each of the dimensions represent areas of strategic decision making, and all four interact and affect each other.